Yee Kididi Kiziha (It is Indeed Pleasing)

A performative transgenerational encounter with togetherness

–

We rejoice in family coming together, in family’s safe arrival. The road, like the forest, can be greedy, claiming several of those who cross its path, and so family’s safe arrival must indeed be rejoiced!

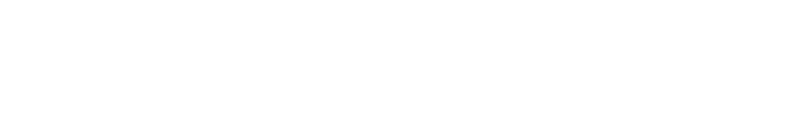

Sitting together in a room that always seems too small to fit all of us, yet never feels small at all since ‘a small house will hold a hundred friends’; a passage from the bible is shared, we close our eyes to pray, and then, we open page 306 of the ChasuChristian hymnal. Our attention is now on song 383, ‘Yee Kididi Kiziha’, together in a chorus we begin to sing.

A score for coming together part I

Out of the chorus bursts a wonderful melody… a wonderfully disorganized melody, realized in distinct yet scattered vocal ranges, perhaps in need of a conductor to set and aid its rhythm… and perhaps, even that is not necessary. Out of the chorus bursts a lineage of voices… voices of my grandparents, my mothers, my wajomba, my brothers and my sisters… voices of my ancestors and ancestress’… voices of my past… voices of my future; a symphony of memory, claimed and unclaimed.[1]

I have often wondered, how this song became so significant and beloved within our (as well as many others’) familial and communal gatherings. Historical archives capture the original/German version of the song as being comprised of four verses. However, the current version which we sing, and which has been translated to Chasu, my mother’s tongue, has been condensed to three verses whose lyrics very simplistically, yet repetitively, attempt to capture how glorious it is for ‘brethren’ to gather in the Lord.

Paying attention to the song’s rhythm, as well as the emotions of those who sing it… emotions which rest somewhere between joy and melancholy; I cannot help but wonder whether the significance of what is conveyed through the rhythm, the lyrics encapsulated in the three verses, as well as in the experience of bringing it to life, perhaps exceeds what meets the ear.

This song, and by extension the Seventh Day Adventist church which introduced it, is rooted in the very problematic history of colonial occupation for the most part of the African continent, the introduction of Christianity and Western education, and embedded to it, a systematic denigration of indigenous ways of knowing, existing, and expressing a world view and its spiritual manifestation. This included, amongst others, attempts to obliterate traditional forms of worship, learning, healing, creative expression and recording history. It is within this background that my sense of wonder extends to the internalized ramifications of this history on those who carried the weight of its actualization and its narrative across generations; and how these feelings are harbored deep within the soul of the song itself… in the emotions evoked by its rhythm… in the breath taken by those who sing it.

In her account of the Wayward, Saidiya Hartman attempts to capture the power of the chorus as tool for “collaboration and improvisation that unfold within the space of enclosure.” By this she means, as a “dance within an enclosure” … a dance which is never ending in its attempts to seek for “a different kind of story”… the kind that questions and challenges the existing narratives related to “the long history of struggle, the ceaseless practice of Black radicalism and refusal, and the tumult and upheaval of open rebellion.” (Hartman, 2019: 384 )

According to Hartman, the chorus, as a polyphonous entity, can propel transformation as “an incubator of possibility” and as “an assembly sustaining dreams of the otherwise.” (Hartman, 2019: 384). Listening to our chorus, and to Hartman’s conceptualization of the chorus, I can’t help but wonder what other stories are harbored deep within this song. What ‘different’ stories can be told which historical accounts have not already told… and what ‘different’ narratives—which go against the typical grain of cower and defeat—can be fleshed out of the many generations of familial and communal gatherings (within the chorus of this song)?

[1] Mjomba (pl. Wajomba ): Maternal uncle (noun)

Two down

One up

Two down

Shode births…

Koko Orupa, who births…

Bibi Mkunde, who births…

Mama Demere, who births…

Me

–

Two down

One up

Two down

Shode becomes my daughter…

Orupa becomes my niece…

And, Mkunde becomes my sister

Rehema Chachage

One up, two down, 2021

Installation

Photographic prints, text, and audio

60 x 90 inches per image

Two down

One up

Two down

A pattern emerges, meticulously weaved on a long Ukili

Two down

One up

Two down

A thread of history is weaved and carried across from generation to generation

The call for coming together

Rehema Chachage

A choreography for coming together part I: The paper

An installation featuring paper, scent,

ash, stones, and video

Paper dimension: 400 x 100 cm

2021

I could not determine the length of the paper in pages or words, because the paper does not use pages or decipherable words. Using the metric system however, I was able to determine that the paper measures to about 4140 cm long by 53 cm wide in dimensions.

The store, from where I purchased the paper, had simply listed it as ‘art paper’. Not much detail was offered. Texture-wise, it is somewhere between a canvas, wallpaper, and cotton paper. Its surface is quite smooth, and deceivingly fragile. But the paper itself is quite agile and does not easily accede to wear and/or tear.

Three previous ‘drafts of writing’ were attempted, in shorter lengths of 1380 x 53 cm, prior to this extended and ‘final draft’. Three sheets of paper initially hung above the fire, but the fire decided that they would never be published. This ‘final draft’ was our second attempt/negotiation with the fire. Thankfully, the fire agreed, we have a paper!

The ‘writing’ itself is done via soot and presents itself in stains of light tan and coffee brown, with ash streaks. The soot was uncontained and uncontrolled. Because of this, the ‘writing’ process took a life of its own, with the soot choosing/deciding where to land on the paper; forming deeper stains on some parts, whilst barely staining other parts of the paper. Some parts miss the soot stains altogether. Instead, they remain with the marks of the raffia code from where the paper hung, or of the scattered ashes that blew from the burning wood.

The paper has footnotes, in the form of scent. A scent reminiscent of that carried in one’s clothes after a visit to the village. This is a lingering earthy scent with notes of wood smoke which capture both the nature of the wood… the split of its heart… as well as the smoke of its burning. For the impressionable nose, the scent is a powerful mnemonic, signaling a retelling of past experiences of spaces that people have lived in over the generations. The sound of that scent, rings truth to these experiences.

Mama Demere writes…

The soot my daughter collected does not compare by any stretch of imagination to the soot I am familiar with. Above and around the heath and kitchen walls in all the homes I have lived in my childhood; there, the color of soot was a texture between tobacco, coffee and dark chocolate. My daughter did not have the privilege of living in any of those homes. She learnt to make wood fire for the first time when she wanted to cure her paper. Even then, community was needed to help her figure out how it is done and how to execute it. The figuring out took a life of its own, a week, or perhaps more. Starting the fire, was a challenge she chose not to live up to. She was happy to let the community perform the ritual, while she learnt and perfected the art of keeping the fire burning and that of regulating the flame.

Looking at my daughter’s creation, collecting soot as an artistic expression, I cannot help but remember Koko Orupa’s kitchen, which also doubled as our community space within her circular hut. There we waited for the evening meal, the only time really that we would converge as a community.

Koko’s kitchen was the smokiest I have ever known.

It is widely believed that the quality of the firewood determines how good the fire burns; and by extension, how much smoke it emits. That may be in other cases, but not in Koko Orupa’s kitchen. Despite her advancing age, she maintained an obsession with the finest firewood, which we had to fetch from the fringes of the earth, literally. She would lead us like flock to the furthest spots in the woods, skirting the cliffs at the edge of our hilly village in search of the driest and finest species of firewood. Walking down the slopes was fun. We would only realize how far we’d walked as we started plying the narrow path back home, heavy leaden with firewood. Negotiating those steep slopes was excruciating. Thorny branches tore into my dress and pricked my tender skin, while sharp rocks sticking out from the earth cracked my toes and tore the soles of my bare feet. Like a lieutenant leading her platoon to battle, she took the lead, her three grandchildren on tow; a walking stick steadied her steps as she slowly walked up the hill. Slowly but surely, one step after another, unfaltering. We were never raised to complain, so we hardly did. With sweat dripping down our brows, we made our humble offering to the Jini residing in Koko’s heath hoping our hut would smoke less. But the Jini was not easy to appease. He devoured the firewood like crazy, but his rage did not subside. It continued to punish us with billows of smoke which he continued to spew from Koko Orupa’s heath.

I know now what I didn’t know then, that the very architecture of my grandmothers’ circular hut was the biggest contributor to our ordeal with smoke. It was dingy, with a tiny window that let in the breeze which was then trapped inside. With no cross ventilation, the breeze circled in the hut in search of the way out and collecting smoke as a billow of dust collects at the eye of the storm. We thus had to brave a constantly smoky and soot filled room no matter how good the fire burned. The walls were soot filled and so was the ceiling under which was perched a rafter right above the heath for curing meat, drying seeds and protecting them from vermin; and keeping kindle dry at all times. The soot under the rafter, however, had a special quality. It grew into strands similar to dreadlocks stubs. Koko would harvest it, soak it in water and make you drink the water whenever you had an upset stomach; and it worked like magic! The wall against which the cooking stones were planted into the earth was equally glittering with coffee brown soot.

A score for coming together part II: 10 movements

–

– Togetherness begins in a car—sometimes in a bus—whose capacity is often stretched to (and many times, beyond) its limits.

We sit together for hours, surviving rough roads which stretch over several kilometers; bodies moving to and against each other, as the car/bus negotiates the swerves, turns, bumps, and potholes that it meets along the way.

– Togetherness happens over conversations, sometimes, over the silences, which fill the hours, which we spend on the road. It is that space between ease, and annoyance, between excitement and dreading. For there is always that one person to delay us for hours…there is always that one year one would rather not go altogether!

– Togetherness is my sister’s head resting on my shoulder, as she gently closes her eyes to take a nap. It is my children’s tiny bodies moving in and out of my arms non-stop; travel always make children restless!

– Togetherness is finding the perfect corner, or a bush from where to ‘dig for medicine’. It is taking turns to stand cover for one another so the ‘digging’ can be semi-private!

– Togetherness are the mid-journey purchases… one must never arrive empty handed!

– Togetherness is the sound of a bus honking as it approaches Maore. It is the excitement of hearing, and running towards, the honk (if you arrived earlier). It is tightly hugging together outside the bus. It is helping with luggage, chatting and laughing while hiking up to Bibi’s

– Togetherness is laughter, prayer, songs, stories, games…

Sometimes, it is annoyance, tears, quarrels, and misunderstandings!

It is the sounds of children playing in the morning, bare feet and bare chested, enjoying freedoms that their ‘city life’ often deprives them of.

It is the sound of the friendly neighbor’s greeting in the morning—Ko Peter, urewedi?

… both a greeting and a (self) invitation to join in in the circle of togetherness …

… both a greeting and an upholding of the moment that marks Bibi’s transition from Mkunde to Ko- (that is, Mother of -) …

… a bittersweet greeting to hear in the present, for Bibi Mkunde will always remain Ko Peter, yet every Ko Peter uttered, is a painful reminder of the fact that Peter, her first born, is no longer with us!

– Togetherness is the sound of masenzo sizzling, or that of rice being scattered inside the Ungo, or that of the up and down motion of Mpingo against the Kinu.

It is the sound of a very crowded Kiete… the sound of bargain during purchase, for every price can and must be bargained down!

– Togetherness are the customary visits to various houses in the village … for it takes a village to raise a child, and even as a grown up, the child must never neglect the community that nurtured them!

It is the discomfort of your overfed body… for every elder you visit will most likely feed you, and refusing to eat is just unpolite!

It is the sadness of having to visit less and less houses as the years pass… for ‘whenever an elder dies, a library burns down’

– Togetherness is Bibi Mkunde and Babu K!

It is the countless visits to the hospital, which we have maintained over the years as a way of managing the ailments that come with their old age.

It is taking turns to look after them.

It is our fingers running through their skin to massage their aging and aching muscles as a way of keeping them comfortable.

It is everyone playing a role (however small) in reciprocating decades of their various ‘labors of love’

It is the silent prayers that the Lord keeps them for they are the glue that keeps us together!